Digital Accessibility Democratising Video Games

Excerpt

Nier: Automata by PlatinumGames is by no means an extremely difficult game. Yet, only 40.9% of players have managed to reach the game’s default ending, according to Steam’s statistics.

This article first appeared in Digital Edge, The Edge Malaysia Weekly on June 28, 2021 - July 4, 2021

Nier: Automata by PlatinumGames is by no means an extremely difficult game. Yet, only 40.9% of players have managed to reach the game’s default ending, according to Steam’s statistics.

Thirty-three-year-old Clinton Lexa not only completed the game and its various endings, but was also ranked fifth on the game’s speedrunning world leaderboard in 2017. He finished the game in about 100 minutes, and he did so with only one hand.

Going by the online persona “halfcoordinated”, Lexa suffers from hemiparesis—the inability to move one side of the body. There are many more gamers like him, such as SightlessKombat and Steve Saylor who play video games blind. There are even professional gamers and streamers with disabilities, such as the deaf Fortnite player Ewok.

Physical disabilities have hardly dampened the intense passion of gamers, but games are not traditionally built with accessibility in mind. It is not uncommon for video games to have hard-to-read subtitles, sequences that require button mashing, or require multiple inputs to perform an action—all of which are not customisable in the in-game settings menu.

One key factor in driving change is the US Federal Communications Commission (FCC) announcing that communication functionality in video games, such as voice and text chats, developed and released from January 2019 onwards would be expected to be compliant with national accessibility standards set by the 21st Century Communications and Video Accessibility Act 2010 (CVAA).

Games partially developed during this period have some leeway, but must reasonably fix these chat accessibility issues. The FCC would also investigate consumer complaints about games that failed to meet the industry standards and have the authority to issue fines against publishers who do not comply despite the complaints.

Although this does not directly affect gameplay, the gaming industry has started paying attention and conversations surrounding video game accessibility are on the rise. The Game Awards even introduced a new category for video game accessibility in 2020, with similar awards mushrooming across the industry.

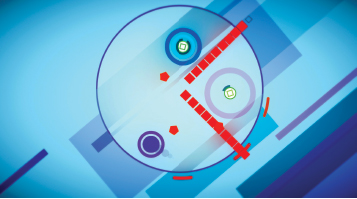

HyperDot, a game where players control a dot by avoiding obstacles. Eye-tracking allows players to control the dot without the use of traditional devices. (Photo by Tribe Games)

Developers Taking Action

It does not take an army of developers to introduce accessibility features. HyperDot, a minimal action arcade game nominated for the aforementioned award, was developed by solo developer Charles McGregor. In the game, players control a dot with the simple task of dodging obstacles.

“Initially, I did not design HyperDot with accessibility in mind,” he tells Digital Edge. “At the time, most indie developers I had interacted with did not really talk about accessibility options, myself included. I was more or less thinking about the default options, such as having colour blind modes, which I had seen in other games.

“It was not until halfway through HyperDot’s development that I began to think about accessibility as a bigger part of the game. One of my friends had won a Tobii Eye Tracker device at a convention, and we joked around about adding eye-tracking features into HyperDot.

“I thought it could be neat and added it in, and had a lot of fun playing the game with the eye-tracking feature. Then, I started to think about how this could help someone who couldn’t hold a traditional controller [to] complete HyperDot in its entirety. I leaned more into it and, with the help of my publisher GLITCH, was able to reach out to the disabled community of streamers and get feedback from them.”

McGregor admits that it is extremely difficult to develop games that are fully accessible to everyone, but that should not stop developers from trying. As a gamer, he feels terrible when he is left out of a game that he wants to fall in love with. As a developer, it feels worse to see players unable to do so due to the lack of accessibility features.

Promotion materials for Watch Dogs: Legion (top) and Assassin’s Creed Valhalla (below). Both games were developed by Ubisoft and were nominated in The Game Awards 2020 for the Innovation in Accessibility category.

From his experience developing HyperDot, he boils down the accessibility portion of the game’s development to two key pillars. The first is flexibility, which includes introducing different game modes, enabling users to quickly jump in and out of the game, and supporting different controllers and having them work seamlessly.

The second is minimalism in the form of art styles and user interfaces, as well as controls and game mechanics that are easy to understand. He says that having these two pillars early in development makes it easier to introduce accessibility features later on.

Ubisoft is another game developer that champions video game accessibility, with titles Assassin’s Creed Valhalla and Watch Dogs: Legion being nominated for their innovation in accessibility features in The Game Awards 2020.

David Tisserand, Ubisoft’s senior manager of accessibility, tells Digital Edge that the benefits of including accessibility features extend beyond just demographics with disabilities.

He says that player demographics are ageing as time passes, and players who enjoyed video games in the 1970s now have longer reaction times, lower vision and less-refined control of their movements. Focusing on accessibility directly ensures that these gamers can enjoy the medium throughout their lives.

“Ubisoft is a company of 20,000 people. From the perspective of the transversal accessibility team, the most challenging part of our work is to make accessibility part of the DNA of everything we do at Ubisoft,” says Tisserand.

“We will only succeed if everyone who is involved in making, publicising and supporting our games makes accessibility part of their day-to-day responsibilities. This requires a great deal of education, organisation and support, which goes beyond the individual features we now commonly see in our games.”

High contrast mode in The Last Of Us 2, which makes it easier to spot enemies for people with sight difficulties (Photo by Naughty Dogs)

Accessibility efforts should not be limited to just traditional console and PC games. PlayerUnknown’s Battlegrounds (PUBG) Mobile is perhaps one of the most popular game titles on mobile devices, being downloaded over 730 million times and grossing close to US$2.6 billion in revenue in 2020.

Rick Li, producer of PUBG Mobile, tells Digital Edge that addressing colour blindness is one of the game’s key focus areas, as this is a condition that affects one in 12 men in the world. Addressing colour blindness is highly relevant, seeing that the competitive game targets the teen and young adult male demographic.

“PUBG Mobile introduced a colour blind mode in November 2019, and this includes changing the display colours for many elements in the game—such as red zone, poison, minimaps and even smoke from an airdrop. This mode enabled a fair and even playing field for users affected by colour blindness,” he says.

Different colour blind modes in PUBG Mobile (Photo by Tencent Games)

Li adds that this feature came about when a player commented on Reddit about finding it difficult to use the red-dot optic, a tool used to aim weapons at enemy players. This led the development team down a rabbit hole of different colour vision deficiencies and finding ways to resolve them.

He also points out the importance of listening to the gaming community for feedback and suggestions on how to make the experience more welcoming and enjoyable for everyone.

Thoughts from an Accessibility Consultant

A key contributor to the gaming industry’s tectonic shift towards accessibility is the growing voice of passionate advocates within the community, as well as insights delivered by accessibility consultants. Digital Edge reached out to Ian Hamilton, a UK-based UX designer and accessibility consultant, who specialises in video game accessibility, particularly for pre-school children with profound and multiple disabilities.

What are your general thoughts on the current state of video game accessibility within the industry?

It has changed beyond all recognition in recent years. Only a few short years ago, the idea of gaming consoles having accessibility settings was a fantasy. Now, every major gaming platform has a whole suite of platform-level accessibility options.

A few short years ago, the idea of triple-A games including even a single accessibility option was considered big news. Now, it’s hard to find triple-A games that do not have a wide range [of accessibility options], such as The Last Of Us 2, which was designed from the ground up to be completely accessible to blind gamers.

A few years ago, the number of full-time employees dedicated to accessibility roles was zero, but now it is nearing 40 people across the entire world. However, it is still in its early days. There have yet to be any games that manage to nail all the basics [of accessibility], and we are a long way from where we really need to be.

What other benefits can be derived from having accessibility options beyond just making the game more accessible to people with disabilities?

If you are thinking about a permanent physical impairment, like having one arm, you are also designing for temporary impairments, like a broken arm, [as well as] situational impairments, like holding a beer or a baby, and [cater to] different preferences and levels of experience too.

This comes across in usage data, with features being used by many people than the core disabled demographic they are designed for. For example, 97% of Far Cry New Dawn’s players played with subtitles turned on, and a third of The Last Of Us 2‘s players [enabling] one-handed control options.

What are the common misconceptions the industry has towards accessibility options?

The common misconceptions are that implementing accessibility is going to be really hard, really expensive, and it means diluting your ideas down to suit less than 1% of the player base who probably do not play games anyway.

Every single one of these statements is demonstrably false. The biggest challenge developers face is leaving it too late to consider accessibility. The earlier they consider it, the cheaper and easier it is [to implement]. But if you leave it late, it can be very hard to go back in and change [it].

For example, The Outer Worlds launched with tiny text, so after player outcries, they went back in to fix it. The work took them three months. If considered early enough in development there is a great deal that can be done for relatively little effort.

Rather than diluting anything down, it means ensuring that your vision is kept intact for as many players as possible, including the over 20% of gamers who experience some kind of disability.

What changes would you like to see implemented to make video games more accessible to the wider gaming community?

The battle for awareness is largely won. It is increasingly hard to find developers who have not heard of accessibility.

But there’s still a lot of work to do on breaking down the misconceptions that we spoke about earlier – on education as part of game development courses, on game development tools like Unity and Unreal, [for them to] include functionality to make developers’ work easier, and on workflow and processes, integrating accessibility as part of the day to day business of making games.

I see it really as refinement, taking the solid start that we have and refining and building upon that, to make accessibility work both easier and more effective. And the more we progress towards that, the closer we get to games being able to reach their full potential.